10.14718/NovumJus.2025.19.2.13

Jorge Enrique León Molina 1

1 Universidad Católica de Colombia

Lawyer, professor, and researcher of the Legal and Social Studies Group "Phronesis," CISJUC), School of Law, Universidad Católica de Colombia, Bogotá DC, Colombia.

jeleon@ucatolica.edu.co.

jeleon@ucatolica.edu.co.

0000-0002-4095-4760.

0000-0002-4095-4760.

* This paper is part of the research work carried out by the author in the Legal and Social Studies Group "Phronesis," attached to the Center for Socio-Legal Research (CISJUC), Universidad Católica de Colombia, within the framework of the project entitled Transdisciplinary Studies of Law: Phase 4.

Received: March 10, 2025

Evaluated: March 27, 2025

Accepted: April 24, 2025

How to cite this article [Chicago]: León Molina, Jorge Enrique. "Why Is a Linguistic

Perspective Useful in the Study of Law? Notes on the Decision-Choice Process in

Specific Cases." Novum Jus 19, no. 2 (2025): 383-405. https://doi.org/10.14718/NovumJus.2025.19.2.13

Abstract

This

article proposes a formalization of the decision-making processes involved in

legal controversies based on the forms of interpretation of the judicial

operator. It shows how such processes, both in easy and difficult cases,

contribute to the formation of both indeterminate legal opinions and possible

worlds in the study of law. Ultimately, it aims to present a logical

alternative to the traditional form of legal dispute resolution, grounded in

syllogistic rules and bivalent structures.

Keywords: linguistic

indeterminacies, possible worlds, election, decision, set, semantics,

pragmatics, preference, interpretation

Resumen

El

presente artículo plantea una formalización de los procesos de

decisión-elección dados en controversias jurídicas a partir de las formas de

interpretación del operador judicial; se muestra cómo tales procesos, tanto en

casos fáciles como difíciles, contribuyen a la formación de conceptos jurídicos

indeterminados, pero también de mundos posibles en el estudio del derecho. Por

último, se pretende demostrar una alternativa lógica a la forma clásica de

solución de controversias jurídicas con base en reglas silogísticas y

estructuras bivalentes.

Palabras clave: indeterminaciones lingüísticas, mundos posibles, elección, decisión, conjunto, semántica, pragmática, preferencia, interpretación

Introduction: Decision-Making, Interpretation, and Law

The purpose of this article is to formalize both the decision theory that encompasses the possibility of arriving at multiple concomitant solutions and

the processes of choosing that tend to satisfy their rational criterion in a specific case.1 From this perspective, decision theory consists of determining the essential elements for decision-making,2 which arise from a motivating state of linguistic indeterminacy, either ambiguity or vagueness,3 where

1. Known states of truth are presented, but all of them co-occur, in the same manner and place; or

2. Unknown states of truth are presented, which must be specified on a case-by-case basis by an interpreter.

The importance of analyzing a theory of decision and choice in the context of law lies in its capacity to address, as Moreso states, the central question of legal positivism: how to identify what is legal in a specific case. This analysis paves the way for understanding the thesis of identifying the social sources of law.4

This

makes it possible to create at least three ways in which it is possible to

identify what is legally relevant and what is not:

1. Formalist

2. Non-formalist or inclusive

3. Neutral5

It

must also be stated that all indeterminacy arises within the framework of an

interpretation; for Larenz, interpretation is a process by which, from a brute

fact, a legally relevant fact is deduced as a statement, which specifies

within itself the content of a certain applicable norm.6 Thus, the problematic meaning arises from the adequacy of the facts to the

literal meaning of the legal corpus that regulates it, or when an

interpretation is sought beyond what is legally determined in that specific

case.7

Problems in interpretation are the product of:

1. Languages with a high load of indeterminacy, which allows, in their designation, for grouping a good number of concomitant facts that can vary according to the universe of the discourse8 used in the specific case.

2. Legal concepts exhibit

polyvalence, as their designation varies among the norms that impart meaning to them.9 Consequently, many legal concepts initially lack specific content and are defined through judicial decisions.10

The fundamental objective of interpretation is to clearly avoid the occurrence of a normative contradiction.11 In principle, any interpretation is based on a legislative text, from which the

meaning of the text in the specific case is to be deduced. This quest for

meaning within the text can be overt or covert and requires exploration by the

interpreter.12 Thus, the interpreter's role is to discern such meaning without introducing new

elements. This task becomes intricate in systematic interpretations, where this

passive approach contrasts with the interpretative practice in judicial

proceedings.

From another perspective, interpretation involves the logical process of aligning the law with the relevant facts, achieved through the use of legal language and

its potential connections to the facts. However, this alignment is not

automatic; it requires the interpreter to establish connections between these

elements and arrive at a plausible conclusion based on the specific

circumstances. Each fact presents an indeterminate number of plausible

interpretations, which vary depending on the issue to be resolved through the

application of the law.13

In this sense, interpreting implies knowing the position of the legal system in a specific case; exactly, what the norm says in the face of a fact. However, when such an answer is not simple, it requires an alternative process for creating a satisfactory response within the legal system that is consistent with its judicial function. Therefore, for Larenz, the process of interpretation is a joint work between jurisprudence and the science of law, where the legal solution of a controversy requires verification by the science of law, so that this solution can, in its execution, be efficient and effective for similar

cases. Therefore, it is relevant to analyze the legal certainty clause, under

which similar cases are treated similarly, implying that similar decisions are

desirable for the legal system.14

On the other hand, according to Ávila, in order to determine the position of a legal system concerning a specific case, one must start from the normative act, as an operation of a

legal system: In this case, the term norm does not constitute either the body

of orders that regulate human conduct, nor the set of orders in a legal system, but the interpretation resulting from the meaning attributed to these corpora.15 This implies that in an interpretation process, a two-way correspondence between provision and norm is not necessary, thus determining that multiple

interpretations of certain facts do not qualify a norm in the strict sense.16

Therefore, the function of the science of law is not only to construct a legal-scientific description of a fact, but also to seek the construction of an interpretation that makes possible the use of a rule, in each time and space, in order to provide a solution to a particular legal controversy; this is achieved through a decision that is coherent and consistent with both the facts and the legal system as a whole.17

Besides, the interpreter's activity in this system is to construct plausible meanings in legal provisions: beyond mere subsumption, or even determining maxims present in application processes in specific cases. It is important to clarify that the search for meaning in an interpretation process is not the same as affirming that there is no solution to the specific case.

From Interpretation to Decision: The Role of the Interpreter

To analyze the relevance of interpretation when deciding, it is necessary to start from the concept of minimum meanings, which are understood as any prior use of language that precedes its ordinary or technical application.18 As antecedents of this concept, for example, we find in Wittgenstein[19] the sense of what, despite having the same language, corresponds to different signs, which constitutes the meanings that preexist the ordinary process of interpretation.20 On the other hand, Aarnio states that these minimal meanings constitute the

meanings that pre-exist in the interpretation process, since they derive from

linguistic stereotypes already existing in speech acts. Finally, we can cite

another relevant process of interpretation, at the head of Heidegger's hermeneutics,21 insofar as it proposes the interpretation of propositions based on pre-existing linguistic structures, on the condition that these structures are incorporated prior to the common use of language.22

From these forms of text comprehension, the interpreter's task is, in addition to seeking the construction of a way of understanding the text, to reconstruct the meaning of a proposition within the framework of a discourse endowed with meaning, even overcoming possible indeterminacies.23 The way in which these processes of interpretation are made practical from the law is in the search for legal meanings of facts relevant to the law; but it

also occurs in cases where they face limits, whether dogmatic, social,

cultural, political or interpretative, that, if violated, could affect the

basic principles of that judicial work.24

In light of the above, interpretation aims to reach the construction of syntactic,25 semantic, and pragmatic connections in the decision and application of legal concepts to contingent realities for law,26 thus setting out the circumstances in which these are carried out and decided at the judicial level. In this function, the interpreter creates the axiological connections by virtue of which facts are linked to norms, and they define the categorization of the latter as rules, principles, or values.27

On the

other hand, within the framework of constructing this form of interpretation, a

court, as an interpreter, may deviate from a commonly accepted use of a legal

term if there are better reasons for such an interpretation provided by

context, specialization, or public policy considerations. For example, it is

common in the study of law to understand that correct interpretations are those

that provide adequate knowledge, are supported by suitable reasons, and are

valid for resolving a legal controversy. This process involves subsuming a

factual consequence under a normative factual assumption.

Thus, it

is necessary to emphasize that there is no correct interpretation, since the

processes of normative interpretation, as stated above, are susceptible to

social change that affects the relations of order of individuals.28 It is here that it becomes evident that every interpretation has a temporal

basis, which justifies its validity29 in the legal order based on its effectiveness in the social order. However,

even if it is justified to move away from the dominant interpretation in

pursuit of social change, it is impossible to completely alter the legal values

underlying the legal order.30

Ultimately, the process of interpretation must seek to both shape31 and determine the scope and content of the law applicable in a specific case32;

this claim clearly justifies the decision-making power of the judicial body.

However, the claim to rectitude that Larenz speaks of, seen from this point of

view, obeys nothing more than a criterion of identity: The statements that are

the product of an interpretation can be adapted both to the legal system and to

the temporal space that is lived in the social order.33

Therefore, interpretation is not only the product of the context in which it is exercised,

but also of the uses of language that are extracted from it;34 and from there, it starts for the construction of a decision.

Linguistic Indeterminacy and Choice

It is

important to note that interpretation as an action is more explicitly evident

in a state of total indeterminacy, where the concept referred to when a legal

solution is sought cannot be shown, as well as states of partial indeterminacy,

where the resolution of a legal problem is not based in any previously

determined logical sense, on the condition that the choice of one of the

alternative answers is not relevant to the others.35

At any of these stages, to give meaning to a proposition, it must be consistent with the set of existing possibilities,36 which are connected within the framework of a particular meaning.37

For example:

C(a) = X38

Where:

C = Case under study

a = Method for resolution

X = Emergent solution

To solve a given legal problem, the methods necessary to cover an emergent solution must

be considered, since linguistic indeterminacy occurs precisely within the framework of plausible solutions. On the other hand, decision operates as a synonym for alternative, in the sense that the set of alternative decisions is equal to the set of alternative actions to the initial ones.39

Thus, choice constitutes an action given by preference, which acquires relevance within the framework of

1. Collision between rules

2. Probability

of a decision-making reason in each context

3. Frequency

or interest of an action

The correct way this process is linguistically evidenced is not when it is said that a decision is made, but rather the fact of reaching a decision, as proof of the action that made it possible.40 For Aarnio, in the exercise of the judicial function, it must be possible to distinguish between two concepts that are often understood as analogical, as an answer applicable to a specific case:

1. Final answer

2. Correct answer

Where the final answer does not necessarily correspond to the only correct answer, because, in a multiplicity of possibilities, the most plausible is chosen.41 In this case, it is necessary to highlight the need for ambiguity in the concept of decision, framed in two versions:

1. Strong decision. Typical of closed legal systems, since it promulgates the existence of a single correct answer, which is discovered in each case.42 In this version, the judge's role is dual; on the one hand, he seeks to find the only correct answer, and on the other hand, he strives to make that answer explicit in the case where it is implicit.43

2. Weak decision. This version implies the existence of a correct answer, but it may or may not be discoverable.44

Furthermore, the correct answer is the main objective of the judicial operator since the

validity of its conclusions must always be based on certain given premises. For Aarnio, the problem of the legal syllogism is framed in the well-known fallibilist dilemma,45 by virtue of which the possibility or impossibility of a correct answer that satisfies its own logical conditions is determined.46

Faced with the problem of the correct answer, Aarnio puts forward two theses that provide a solution to the fallibilist dilemma:

1. Ontological thesis: There is no correct answer within the framework of legal reasoning.

2. Epistemological thesis: The semantic ambiguity of the case prevents finding a single correct answer.47

These theses present a problem in their enunciation, as within the specific case framework, there is no legal security that allows for the full identification of rights and duties.48

As said, the position defended by Aarnio is based on a necessary ambiguity since there must be a need for imprecision of the normative precepts to avoid possible conflicts. Aarnio even affirms that, in Alexy, the idea of sustaining the thesis that there is only one correct answer based on rational discourse is also evident, which ultimately makes the thesis of relative correctness feasible.49

Therefore, the choice of the solution to the specific case depends not only on reasoning, but also on evaluations.

The coherence clause of the possible solutions is based on the comparison of the relative weights of each of these alternatives; Aarnio determines the impossibility of weighing such final reasons since the coherence between them is the product of the choice of the most appropriate one.50

Thus, it is established that the beginning of all legal reasoning is in the determination of the options or alternatives to respond to the problem raised,51 according to three postulates:

1. Ethical values

2. Moral principles

3. The interpretation of cases

Therefore, the approach of a single decision52 is based on

1. Conviction:

if it arises because of a rational discourse.

2. Persuasion: if it is a non-rational formulation of an opinion.53

Evaluations, understood from this perspective, are relevant if they have a certain level of generality,54 which implies that they have an abstract or impersonal relationship with their content, as a condition of objectivity in the face of the subject they deal with.55

Normative Arguments, Secondary Indeterminacies, and Decision-Choice Process

On the

other hand, the interpretation of prima facie (prior to experience) arguments,

which constitute certain types of normative constructions, is always relative

to the criteria that contextualize them; these are time, manner, and place.56 Such arguments arise from their generality since they are understood as

starting points for subsequent assessments that give rise to a decisive

argument in the specific case.57 Thus, contextualizing a prima facie argument produces the emergence of ideal

audiences endowed with rationality; that is, explaining a set of general

situations produces the emergence of rational subsets that give meaning to that initial set.58

The

solution resulting from an interpretation produces a logical decision, which

consists of linking the state of indeterminacy of a legal concept with the act

of selecting an alternative solution to it, through a set of logical operations that justify that relationship, thus reducing the initial level of indeterminacy.59

Secondary indeterminacies are the product of the operations given between the recognition of the initial problem and its final resolution.60 From these indetermi-nacies, the process of decision-choice based on an action has two forms:

1. Pure decision: Where the action that arises from the composite mixture of selection processes that are knowable and identifiable by a given environment constitutes the decision-choice process.61

2. Pure choice: Where the action composed of determined processes resulting from elements difficult to identify constitutes the object of the decision-choice.62

Thus, the logical formalization of these indeterminacies63 is posed as follows:

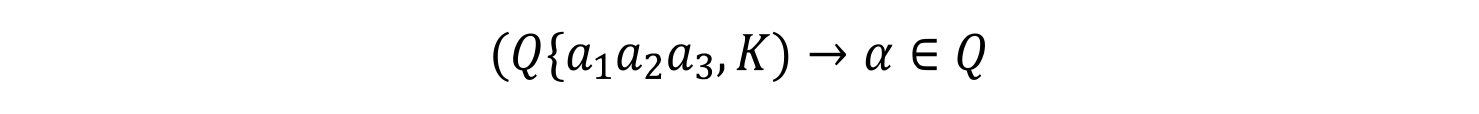

It is important to note that the functor 6 establishes a sufficient index for the choice,64 so that Q presents alternatives of plausible decision: a1, a2, a3

Q = a1a2a3

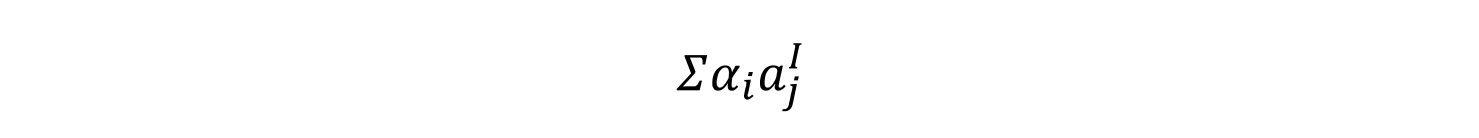

Such alternatives determine that for every decision, a set of pure choices is also necessary, with identity values i and j,65 as follows:

For example:

α = Case under study

Q = Sequence of indeterminacies (possible alternatives) a = Solution possibilities

a = Solution possibilities

θ = Multiplicity of ways in which Q solves X with values determined by each possibility

If at any time 0 is indeterminate or unidentifiable, then the process produces a partial decision; that is, one that concerns special points of the problem to be solved.66

Within

these languages, the choice of an action does not necessarily imply that there

is an execution. Thus, the total decision is understood as the set of

possibilities67 that can be selected for a decision, which is, in many cases, subject to unforeseen events that confirm or defeat such possibilities as contingencies; therefore, if the selection is reconsidered between selection and execution,

another selection process is triggered.68

Conclusions

Within

the processes of interpretation, the absence of empirical verifications of the

legal postulates that support them is evident, to the extent that bivalent

decisions, in accordance with the convenience of systematic interpretations,

produce a legal solution based on syllogistic elements.

This

decision does not correspond to a real process, as the legal analysis of

decision making processes has logically demonstrated that different valid and

effective alternatives for solving the specific case are presented.69 Thus, it overcomes that classic positivist specter of a solution to a legal

controversy. Therefore, as stated in this article, it is necessary to use

polyvalent logics, which give meaning to the multiplicity of determined or

possible model sets, which solve the different legal controversies, whether in

easy or difficult cases, or similarly, in cases of linguistic indeterminacies

resulting from interpretations of specific cases in the light of the law.70

The

proposal now is to demonstrate how these logical decision-choice processes

underpin how decisions are made within the framework of the judicial function,

considering that the facts, as foundations of the effective structure of the

law, amplify the interpretative spectrum thereof. This proposal serves as the

starting point for a new, multipurpose approach to interpreting law.

Notes

1 Jens Allwood, Lars Gunnar Anderson, and Õsten Dahl, Lógica para Lingüistas (Madrid: Editorial Paraninfo S.A., 1981), 32. The theory of possible worlds is studied from the notion of model sets, since "for every proposition we can find a set of possible worlds in which the proposition is true. We will call this set the truth-set of the proposition. [...] Correspondingly, a possible world can be characterized as the set of propositions which are true in it (and thus describe it)."

2 Paulo Suarez, "Smartjustice, process and evidence: special reference to its use in the court of appeal," Revista Brasileira de Direito Processual Penal 10, no. 2. (2024), 5, https://doi.org/10.22197/rbdpp.v10i2.1006. By the way,

"decisions are based, in some way, on objective or quantifiable data. In

this sense, big data manifests itself as an infinite substratum of

information that can and should be used for the adoption of such decisions,

sometimes as simple as the control of urban traffic or the management of public services."

3 Chaim Perelman, El Imperio Retórico: Retórica y Argumentación (Bogotá

D.C.: Norma S.A., 1997), 29. It is important to note that, as Perelman says,

every process of linguistic interpretation "takes place in a natural

language, in which ambiguity is not worked out in advance."

4 Serena Quattrocolo, "An introduction to AI and criminal justice in Europe." Revista Brasileira de Direito Processual Penal 5, no. 3. (2019), 1523, https://doi.org/10.22197/rbdpp.v5i3.290. Given the huge amounts of information analyzed by an expert system, both the input variables of said system and the information they contain must be considered, "but also new investigation systems, based on mining and analysing huge sets of available data."

5 Robert Alexy, El concepto y la validez del Derecho (Barcelona: Gedisa S.A., 2013), 21. According to Alexy, within the definition of law, two theses can be presented: separation and linkage. The former affirms that there is no necessary connection between law and morality in the framework of the definition and applicability of law. The latter asserts that there is a connection between moral and legal elements in the pursuit of an operational definition of law. In any case, "[both theses] are supported by a normative argument when it is stated that the non-inclusion or inclusion of moral elements in the concept of law is necessary to achieve a certain objective or comply with a certain norm."

6 Karl Larenz, Metodología de la Ciencia del Derecho (Barcelona: Ariel S.A., 1994),

308. Thus, interpreting is "a mediating act by which the interpreter

understands the meaning of a text that has become problematic."

7 Alexy, El

concepto, 28. The thesis of inclusive positivism formulates, in its

structure, the inclusion of elements external to the purely normative ones when

constructing an operative concept of law to the extent that there may be

social, political, cultural, scientific, or moral elements in the strict sense,

which can contribute to the solution of a legal dispute. Therefore, "a

purely positivist concept of law is arrived at if it totally excludes material

correction and aims only at legality in accordance with the legal system and/or

social effectiveness."

8 Carlos Alchourrón y Eugenio Bulygin, Sistemas Normativos (Buenos Aires: Astrea

S.A., 2013), 15. According to Alchourrón and Bulygin, the universe of discourse (UD) is understood as "the

set of all the elements (states of affairs) identified by a certain

property." This means that this set groups an X number of states of

affairs that: a) belong to such a universe of things and are elements of that

same state of affairs; and b) have common elements that are called defining

properties. As an example of a), we can say that men are human beings, and as

an example of b), we can affirm that all those who are born in Colombia are Colombian citizens.

9 An

example of these problems is in the legal terms used in different laws or even

in the same law, but with a different meaning: the concept of malice. From

civil law, Fraud implies financial liability, while from criminal law, it

entails punitive liability.

10 Alf Ross, Lógica de las normas (Madrid:

Tecnos S.A., 1971), 21. In this regard, Alf Ross

identifies two types of normative concepts that have an impact on the study of

law: imperatives and indicatives. The former constitute duties that lack

factual content, in that they express the commission of an action in diffuse

temporal and spatial spaces. The latter are contextual duties in time, manner,

and place. Thus, "propositions are devoid of content as long as their

semantic meaning is not clear. On the other hand, they are indicative in the

sense that they contain an idea of a subject conceived as real."

11 Larenz, Metodología de la ciencia, 309. This implies that the mission of interpretation is "To answer questions about

the concurrence of norms and concurrence of regulations, to measure in a very

general way the scope of each regulation, and to delimit the spheres of

normative regulation from each other whenever this is required."

12 Eugenio Coseriu, Introducción a la lingüística (Madrid: Gredos S.A., 1986), 51. The problems of language lie in its ability to transmit as much information as possible, and that this transmits, in the clearest possible way, the meaning that the sender gives to the words used. "In fact, language is a highly complex phenomenon: It presents purely physical (sounds), physiological, psychic, logical, individual,

and social aspects. Consequently, according to the philosophical orientation

(explicit or implicit) of linguists and language theorists, one or the other

aspects stand out, which is often considered predominant to the detriment of

the others.

13 Larenz, Metodología de la ciencia, 310. It is then determined that "each new interpretation of a norm, made by a court, insofar as it will serve as a model for subsequent judicial decisions, changes the effective application of the norm in practice."

14 David Deutsch, La estructura de la Realidad (Madrid: Anagrama S.A., 1999), 15. From here, we can infer that it is from the use of normative language that jurisprudence can reach that predictive level. Through the normative languages in factual contexts that determine its validity, it is stated that "explanations often provide predictions, at least in principle. Indeed, if a thing is, in principle, predictable, a sufficiently

complete explanation of that thing must also, in principle, make (among other

things) complete predictions about it."

15 Humberto Ávila, Teoría de los Principios (Madrid: Marcial Pons S.A., 2011), 29. This implies affirming that "there is no correspondence between norm and provision, in the sense that whenever there is a provision, there will be a norm; or whenever there is a rule, there must be a provision that serves as a support."

16 Robert Blanché, Introducción a la lógica contemporánea (Buenos

Aires: Carlos Lohre, 1963), 98. Blanché defines the calculus of propositions as transitioning from a bivalent

notion to a plurivalent one, which involves overcoming the classical values of

truth and falsehood and extending beyond the intuitive sense of the

systematicity of classical logic. Therefore, "a statement is no longer

categorically affirmed as true or false, taking into account the intermediate

values of certainty [and probability] that fall on those objects that no longer involve a binary analysis."

17 Marta Cabrera, "Aplicación de la inteligencia artificial a la toma de decisiones judiciales," Eunomía: revista en cultura de la legalidad, no. 27 (2024), 27, https://doi.org/10.20318/eunomia.2024.9006. The delimitation of expert legal systems represents the ideal mechanism to support the use, application, and delimitation of AI tools in automated judicial decision-making; therefore, it is stated that "specifically, expert legal systems originated with the idea that they would be able to represent, through formal language, the regulations of a legal system. Thus, they served to emulate the knowledge that a human expert in this field would have"; Jorge León, "El tangram del Derecho: neguentropía y proceso jurídico," Novum Jus 18, no. 1: 190, https://doi.org/10.14718/NovumJus.2024.18.1.5.

18 Roderick Chisholm, "Lenguaje, lógica y estados de cosas," en Lenguaje y filosofía, ed. Sidney Hook (México D.F, Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1982), 340. These meanings can also be understood as the common uses of language, also

known as natural languages. However, to understand its uses in logic, Chisholm

proposes three ways of analysis: a metaphysical one, which corresponds to the

identity of abstract entities in the form of propositions; a psychological one, which obeys the determination of laws of thought; and a linguistic mode, which determines the apophanic qualification of the entities represented. Thus,

"the relationship between logic and language obeys the status of this

class of opinions in the face of the question of whether or not there are

possible plausible alternatives to them."

19 Ludwig Wittgenstein, Tractatus logico philosophicus (Madrid: Alianza S.A., 1997), 41. When there are signs that correspond in form, but have different objects of interpretation, the interpreter's task is to understand the meaning of their designation. As Wittgenstein says in 3.323 of the Tractatus: "In ordinary language it happens with singular frequency that the same word designates in different ways and manners—that is, that it belongs to different symbols—or that two words designating in different ways and manners are used externally in the same way in a proposition."

20 Paul Ricoeur, Teoría de la Interpretación: Discurso y Excedente de Sentido (Madrid: Siglo XXI S.A., 2006), 36. Ricoeur shows us that the ultimate meaning of all interpretation is to highlight how something contained in each

text is known; therefore, "understanding a text, then, is only a

particular case of the dialogic situation in which someone responds to someone

else."

21 Martin Heidegger, El Ser y el tiempo (México D.F., Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2018), 223. In this sense, Heidegger starts from the fact that the ontic reality of the subject determines the way in which he knows how these realities affect him; thus, "the concept of 'reality' has, according to this, a peculiar primacy in the sphere of ontological problems. This primacy

closes the way to a genuine analytic existence of the 'being there' and even

prevents the gaze from being directed to the being of what is immediately 'at

hand' within the world."

22 Ávila, Teoría de los Principios, 31. Ávila, quoting Reale, brings up the subjective a priori condition present in such minimal

meanings as "those pre-existing structural conditions in the process of

cognition, which make the subject interpret something prior to what is

presented to him to be interpreted."

23 Ávila, 32.

From this perspective, "to interpret is to build from something, that is,

to reconstruct: the first because it uses normative texts as a starting point

[...]; the second, because it manipulates language in pursuit of an individual

intellectual process."

24 Franz von Kutzchera, Fundamentos de Ética (Madrid: Cátedra S.A., 1989), 46. The postulate of Generalitat in these lines states that a certain action may or may not be ordered for a group of individuals if, in a similar situation, the same thing is ordered. This postulate is expressed in the sense that "moral judgments [and legal judgments, in this case] can be based on general principles that, as such, make no distinction between individuals. So, if a person A, with these and those characteristics in this or that situation, must do something, it follows that

each of the other persons B, with the same characteristics and in the same

circumstances, must do the same."

25 Solomon Marcus, Edmond Nicolau, and Sorin Stati, Introducción en la lingüística matemática (Barcelona: Editorial Teide S.A., 1978), 57. From axiomatic-deductive

linguistics, this construction implies an exercise of problematization and

automation of the uses of language in the definition of an instrumental sense

of semiotic relations in the study of science; therefore, in the case of law,

"logical models are elaborated, deductive theoretical constructions that,

precisely, in their unilateral character, reveal more deeply the structures of

phenomena in a more precise way."

26 Tzvetlan Todorov and Oswald Ducrot, Diccionario enciclopédico de las ciencias del lenguaje (Madrid: Siglo XXI S.A., 1998), 48. It is important to clarify

that the purpose of the construction of all languages is to explain

semiotically a phenomenal reality: In the syntactic form, the greatest number

of semantic contexts are grouped in the body of the descriptive language of a

given knowledge. Therefore, "to study a language is, above all, to

assemble a set with the greatest possible variety of utterances actually

emitted by an agent at a given time, and thereby to make regularities appear in the corpus [of language], to give the description an orderly and systematic character, and to prevent it from being reduced to a simple inventory."

27 Ávila, Teoría de los Principios, 33. Ávila thus defends the interpretative activity as a reconstructive activity, given that

"the interpreter must elucidate the constitutional provisions in order to

make explicit their versions of meaning in accordance with the purposes and

values within them, shown in constitutional language."

28 Larenz, Metodología de la ciencia, 311. This

implies that " [interpretation] always has a reference of meaning to the

totality of the respective legal order and to the standards of evaluation that

serve as a basis for them."

29 José Luis Serrano, Validez y vigencia: La aportación garantista a la teoría de la norma jurídica (Madrid: Trotta S.A., 1999), 24. According to Serrano, a given norm is valid if it complies with the

formal and procedural conditions that have been determined in its creation,

such as competence and procedure in the case of formal ones, as well as

coherence in the case of substantial ones. The former are based on factual

requirements, while the latter are based on respect for the legal system. Thus, "validity would be provisionally definable as the quality or status of

those norms in force that meet the requirements established in another norm in

force in a legal system."

30 Francisco Fernández, "The future of court's procurators with the advent of artificial

intelligence technologies," Oñati Socio-Legal Series 14, no. 6 (2024), 1587. This involves the creation of sets of decision alternatives that, in any case, constitute a body of decisions applicable to one or several possible cases, where "they try to imitate human logical behavior in each area of knowledge. It adds that these Expert Legal Systems imitate legal reasoning, solving

intelligently, i.e., drawing conclusions from the application of legal rules or

obtaining a general rule from precedents. Likewise, it points out that the

basis of the expert system in the legal field is constituted by jurisprudence

and legislation, with the purpose of providing a legal solution to a legal

problem posed."

31 Javier Aracil, Introducción a la dinámica de

sistemas (Madrid: Alianza S.A., 1978), 40. Any

modeling of the operations of a system at each time involves the construction

of both its causal operations and the determination of the ends that are

sought. "In the study of a system, it may happen that the fundamental

characteristic that is of interest is its evolution over time and,

specifically, how the interactions among the parts determine that

evolution."

32 José Juan Moreso. Lógica, argumentación e interpretación en el Derecho (Barcelona:

Editorial UOC, 2005), 122. In line with the above, the judicial application of the law must formalize a statement of reasons for the meaning of the judgment, that is, the justification of the preference in the choice of an alternative solution, because "the interpretation of the law is a necessary step for its application. There is no application without interpretation."

33 Giselle

de la Torre and Ferney Rodríguez, "Artificial intelligence: A new reasoning method for legal science," Procedia Computer Science, no. 251 (2024), 810, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2024.11.189. This

is only possible if there is trust and confidence in those who exercise the

decision-making function, such as those who resort to the legal system

exercising their right of action; therefore, "given that decisions based

on reasoning by AI & D can significantly impact those involved, AI & D algorithms and language models must base their reasoning on transparency,

ensuring coherence and fairness in decisions, all within a well-structured

meta-normative framework."

34 Richard Rüdner, Filosofía de la ciencia social (Madrid:

Alianza S.A., 1973), 80. As a presupposition of the involvement of

scientific methods in the study of social knowledge, Rüdner proposes the concept of partial formalization to "determine how

theories are considered deductive systems, connected by the common definition

between their statements and their common operations."

35 Michael Arbib, Cerebros, máquinas y matemáticas (Madrid: Alianza S.A., 1982), 23. This can also be understood in the form of the construction of modular

networks n, constituting models of input m and only one output r, where,

even though there is an x amount of inputs and Xn+1 analysis

processes (or operations), there is only one

plausible output n. Therefore, "the state t of an operations

network is only known if the operating modules are known at a given time, which

can also be seen as 2n possible states."

36 Allwood et al., Lógica para Lingüistas, 33. Such possibilities obey, in logical terminology, what Leibniz called "possible worlds," which are those sets where a circumstance or operation occurs, and which are alternative to the set initially analyzed. In other words, it "constitutes the formalization of the best of the possible worlds, where operations of another set are described that, in one way or

another, are true in a given situation."

37 José Juan Moreso, "Las ficciones en Jeremy Bentham: El método de la paráfrasis," Doxa: Cuadernos de Filosofía del Derecho, no. 3 (1986), 132, https://doi.org/10.14198/DOXA19863.09. In the framework of linguistic indeterminacies, a

significant challenge lies in determining a clear proper name for each

phenomenon that occurs in each operation, which broadens the spectrum of

interpretation of a system in the face of a specific problem. However, although this is the claim in the case of law when it seeks to provide a solution to the application of the legal system in reality, "the fact that there is a name in a given speech does not guarantee the existence of an alleged object designated by that name."

38 Juan Gómez, "Inteligencia artificial y neuro derechos: retos y perspectivas," Cuestiones Constitucionales 46 (2022), 98, https://doi.org/10.22201/iij.24484881e.2022.46.17049. Within

this formulation, we can exemplify the following: C represents the legal

problem, a refers to the method by which such a problem is solved, and X

denotes the decision in the specific case. Thus, if Mary was unfaithful to

Peter (C), and infidelity is grounds for divorce (a), then Mary can divorce

Peter (X). Here, the sense of "application and determination of how an

automated decision is reached" is evident.

39 Douglas John White, Teoría de la Decisión (Madrid: Alianza S.A., 1972), 14. Thus, alternative actions "identify ambiguities or vagueness and

the resolution of them constitutes the decision process, arriving at X, which

would be the decision as such."

40 White,

15. The relationship between the concepts of decision and choice can be

summarized as follows: "There can be Choice without Decision, but there

can be no Decision without Choice."

41 Roger

Campione, "The legal-digital metamorphosis of the individual," Philosophies 2, no. 10 (2024), 3, https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies10010002. Considering that "the reason for the reflections that follow lies in the problematic relationship between two powers that shape reality: law and techno-science. And in principle, such powers make up reality by acting like two poles of a battery, that is, having opposite charges: Techno-science is a mechanism of overcoming the limits that human beings find in their relationship with nature."

42 Aulis Aarnio, "¿Hay respuestas correctas para los casos difíciles? Observaciones sobre el razonamiento jurídico racional," Revista de las cortes generales 1, no. 53 (2001), 200, https://doi.org/10.33426/rcg/2001/53/747. This

strong version presents "axiomatic assumptions denoting the plausible

response."

43 Antonio Ester, "La inteligencia artificial en la justicia: desafíos y oportunidades en la toma de decisiones judiciales," Anales de la cátedra Francisco Suárez, no. 59 (2025), 322, https://doi.org/10.30827/acfs. v59i.31404. The determination of the alternative decision in turn implies overcoming a cognitive gap in relation to the knowledge of the process, where the

juridical artificial intelligence "is defined as the set of artificial

intelligence tools designed and/or used for the automation of various legal

tasks, from the challenges involved in the development of said tools to the

peculiarities of legal reasoning."

44 Aarnio,

" ¿Hay respuestas correctas?" 201.

Aarnio, quoting Wroblewski, defines this version as the "ideological basis

of the legal problem."

45 Von Kutzchera, Fundamentos de Ética, 47. To understand this dilemma, it must be borne in mind that the

formulations of normative actions constitute intensional predicates, insofar as

such normative formulations foresee modes of action and their ontological

validity is based "on the possibility of the non-existence of general

criteria that encompass the totality of generalizable statements."

46 Ian Stewart, Conceptos de matemática

moderna (Madrid: Alianza S.A., 1977), 139. To understand this within the formal sciences, we speak of systems of

axioms as models of deduction, where "if such conditions are

satisfied, then such and such things are fulfilled [...]."

47 White, Teoría de la Decisión, 23. The

state of indeterminacy is a state in which there is a well-determined set of

alternatives; however, White, quoting Bulliger, indicates that "a person

is never sure what it is that he is really deciding."

48 Aarnio, "¿Hay respuestas correctas?" 202. In this case, according to Altman, as quoted by Aarnio, the legal authorities that provide such principles "come from a convention."

49 Alexy, El concepto y la validez del Derecho, 81. This postulate arises from the adequacy of a decision based on the discussion of the nature of the principles to the tenor of the iuspositivist model. As long as

the principles are clearly determined by law, there are no underlying

interpretative problems. These arise to the extent that the principles require

judicial recognition because "when these principles or their numerous

sub-principles are relevant in a doubtful case, the judge is legally obliged to carry out an optimization referring to the specific case."

50 Aarnio, "¿Hay respuestas correctas?" 203. In this sense, "interpretation is

a creative process that produces new ways of reasoning all the time."

51 Aarnio,

205. So, "every argument, in fact, is subject to the so-called 'Open

Question,' that is, it can be discussed by a group of rational

interlocutors."

52 Milagros Otero, "El poder judicial frente al problema de la única respuesta correcta," Anales De La Cátedra Francisco Suárez, no. 59 (2025), 420, https://doi.org/10.30827/acfs.v59i.30600. This is because "we must start from the premise that our legal system must provide a final answer to every issue in which the attribution or denial of a right is discussed. It must do so in compliance with the constitutional mandate, according to which judges must decide what is fair in each specific case."

53 Perelman, El Imperio Retórico, 30. At

this point, Perelman shows that the meaning of argumentation, as a process of

transmitting ideas between subjects, is based on the way in which such ideas

are part of a rational environment. "Since the purpose of an argument is

not to deduce the consequences of certain premises, but to produce or increase

the adhesion of an audience to the theses that are presented to its assent, it

never develops in a vacuum."

54 Estefanía Segura, "Inteligencia artificial y administración de justicia: desafíos derivados del contexto

latinoamericano," Revista de Bioética y Derecho 58 (2023), 63, https://doi.org/10.1344/rbd2023.58.40601. One of

the challenges that information technologies face in the judicial process is

"generating integrated and transversal structures, capable of overcoming current schemes, which are mostly focused or

subsidiary, and which have become unavoidable within the current legal

culture."

55 Aarnio, "¿Hay respuestas correctas?" 206. Thus, "the more

general the way in which standards of this kind are given, the more easily they

obtain [widespread] acceptance."

56 Ettore Battelli, "La decisión robótica: algoritmos, interpretación y justicia predictiva," Revista de Derecho Privado 40 (2021), 49, https://doi.org/10.18601/01234366.n40.03. To

optimize judicial decision-making as an algorithmic operation, the

system must adhere to the operative clauses. "In particular, standardizing

the motivation behind the decision is a first step toward the possible

'standardization' of decisions made by judges who rely on the expert

system."

57 Gladys Palau, Introducción filosófica a las lógicas no clásicas (Barcelona: Gedisa S.A., 2002), 135. Whereas, bivalence would not guarantee the

processes of prediction of future elections, nor would it be consistent with

the inclusion of possible worlds since "either statements about the future have more than one truth value and, therefore, the principle of bivalence (PBV) and, consequently, the principle of excluded third must be abandoned; or it is accepted that future contingents also behave according to the PBV, with the

consequent danger of falling into determinism or fatalism."

58 Aarnio,

"¿Hay respuestas correctas?" 207. This suggests that

evaluative points of view are intersubjective because "they are not

limited only to individuals but encompass the common world that we all have as

society."

59 Adam Schaff, Ensayos sobre filosofía del lenguaje (Barcelona:

Ariel S.A., 1973), 84. In turn, Schaff affirms

that the use of language contains indeterminacies inherent to its use as a

communication system; this implies that "such [communicative] difficulties are, among others, those that suggest that language should not only be an instrument, but also the object of scientific investigation."

60 Joan Rovira and Ana Gálvez, "Artificial intelligence and the production of judicial truth," Theory, culture and society 42, no. 1 (2025), 14, https://doi.org/10.1177/02632764241268174. Such recognition is "given in the framework of."

61 León, "El tangram del Derecho," 151. However, it is important to keep in mind that both choice and decision orbit around the concept of preference, which implies the action of decision-making in a specific case around the plausible alternatives of solving a concrete case. "The meaning assigned to a concept is a decision to serve certain interests, which determine the plausible result; so, the reduction of indeterminacy is the product of decidability in the specific case."

62 Óscar Agudelo, "La paradoja de la racionalidad lingüística: el lenguaje jurídico claro desde una variación de la teoría matemática de la comunicación," Novum Jus 17, no. 3 (2023), 310. Also, we can speak of possible worlds when reaching a decision, where the possibility of the existence of alternative model sets to those initially described is understood. However, "another simple way of seeing possible worlds is with the what-if clause, which questions what the real world could be like under another course of decision."

63 Patricia García, "Inteligencia artificial, predicciones y funciones normativas," Teoría y Realidad Constitucional, no. 54 (2024), 423. Where

the following metalanguage is presented:

Q = State of knowledge/result set

K = Pure decision process

θ = Identifiable cognitive operation

q = Result

However, correlation refers to "the correspondence between two or more actions or phenomena. Two variables are correlated when variations in one of them cause the other to vary, either upward or downward. There will be a correlation between A and B if, as A decreases or increases, B also increases."

64 Antonio

Martino, "The Digesto Jurídico Argentino: Considerations Concerning a Large Juridical Project," in Language, Culture, Computation: Computing of the Humanities, Law, and Narratives, ed. N.

Dershowitz and E. Nissan, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 8002 (Berlin

and Heidelberg: Springer, 2014), https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-45324-3_18. As an example of this formulation, we could note that within the multiplicity of ways of extinguishing an obligation (Q, K), in the case of paying the obligation incurred by Mary to Peter (q), such obligation is extinguished (Q). Thus, "the multiplicity of paths paves the way for solutions that can be addressed in favor of a decision."

65 In the

same example of the obligations above, the set of all forms of extinction of

obligations (Σ)groups all the possibilities in which the same result can occur (i, j) in the case of Mary and Peter (α).

66 Cristian Díez, "Voluntad y motivación en actos administrativos

automatizados con inteligencia artificial. ¿Un

nuevo entendimiento de conceptos humanos?" InDret 4

(2024), 415. Thus, extinguishing an obligation (Q) consists of paying,

transacting, or novating (a1, a2, a3) a certain debt, which implies that if

Mary pays what is owed to Peter, then she extinguishes the obligation. This

example shows how there can be "several solution possibilities, which

coexist in the same specific case."

67 Gilbert Harman, Significado y existencia en la filosofía de Quine (México

D.F: UNAM, 1983), 14. The set of solution possibilities is presented as

an alternative to the problem initially posed. This set supposes the

construction of several propositions that deal with such a problem, whose

identity qualifies the propositions according to their inclusion in such a set,

and their containment occurs in relations of true inclusion or non-inclusion

within their structure. "It is said that a sentence expresses a necessary

truth if, given the meaning of the sentence, it must be true no matter what; and

a sentence expresses a truth a priori if the knowledge of its meaning can be

sufficient for the knowledge of its truth."

68 J. M. Mardones, Filosofía de las

ciencias humanas y sociales: materiales para una fundamentación. (Barcelona: Anthropos S.A., 1991), 237. This

operational reduction is due, as Mardones says, quoting Lühmann, to the complexity in the processing of incoming and outgoing

information from a given system. The identification of such elements occurs

when "it is the product of the two concepts of complexity [reductionist

and indeterministic]. This indicates, therefore, that systems do not understand their own complexity (and even less that of their environment) and can instead

problematize it. The system, on the one hand, produces, and on the other, it

reacts to a blurred image of itself."

69 Jhonatan Peña, "Inteligencia artificial para la seguridad jurídica. Superando el problema de la

cognoscibilidad del derecho," Revista oficial del Poder Judicial 14, no. 17 (2022), 104, https://doi.org/10.35292/ropj. v14i17.568. The delimitation of algorithms in judicial decisions is not arbitrary,

but rather obeys an exercise of delimiting normative variables that serve to

provide emerging solutions to specific cases. "Thus, through the

development and use of AI tools, the path of normative production will probably

be redesigned, that is, better conditions will be obtained that allow

understanding the current regulatory framework and the information regarding a

factual situation to be legislated."

70 Carlos Maza, Aritmética y representación: de la comprensión del texto al uso de

materiales (Barcelona: Paidós S.A., 1995), 141. The

principle of systematicity proposes a logical alternative for choosing

preferences when establishing both relationships between quantities and the definition of preferential alternatives to problems submitted to the study of a formal system since "the principle of systematicity [implies a] logical conclusion of the hypotheses that sustain both a theory and the system of knowledge connected in a manner consistent with the system that studies the problem analyzed."

References

Aarnio, Aulis.

"¿Hay respuestas correctas para los casos difíciles? Observaciones sobre

el razonamiento jurídico racional." Revista de las Cortes Generales 1, no. 53 (2001): 199-222. https://doi.org/10.33426/rcg/2001/53/747.

Agudelo, Óscar. "La paradoja de la racionalidad lingüística: el lenguaje jurídico

claro desde una variación de la teoría matemática de la comunicación." Novum Jus 17, no. 3 (2023): 301-28. https://doi.org/10.14718/NovumJus.2023.17.3.11.

Alchourrón, Carlos, and Eugenio Bulygin. Sistemas

Normativos. Buenos Aires: Editorial Astrea S.A., 2013.

Alexy, Robert. El

concepto y la validez del Derecho. Barcelona: Ed. Gedisa S.A., 2013.

Allwood,

Jens, Lars-Gunnar Andersson, and Òsten Dahl. Lógica para Lingüistas. Madrid:Editorial Paraninfo S.A., 1981.

Aracil,

Javier. Introducción a la dinámica de Sistemas. Madrid: Alianza

Editorial, 1978.

Arbib, Michael. Cerebros, máquinas y matemáticas. Madrid: Alianza

Editorial, 1982.

Ávila,

Humberto. Teoría de los Principios. Madrid: Marcial Pons S.A., 2011. https://doi.org/10.2307/jj.2321986.

Battelli, Ettore. "La decisión robótica: algoritmos, interpretación y justicia predictiva." Revista de

Derecho Privado 40 (2021): 45-86. https://doi.org/10.18601/01234366.n40.03.

Blanché, Robert. Introducción a la lógica contemporánea. Buenos Aires:

Ediciones Carlos Lohle, 1963.

Cabrera,

Marta. "Aplicación de la inteligencia artificial a la toma de decisiones

judiciales." Eunomía: revista en

cultura de la legalidad, no. 27 (2024): 183-200. https://doi.org/10.20318/eunomia.2024.9006.

Campione, Roger.

"The legal-digital metamorphosis of the individual." Philosophies 2, no. 10 (2025): 1-25. https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies10010002.

Chisholm, Roderick. "Lenguaje, lógica y estados de cosas." In Lenguaje y filosofía, edited by

Sidney Hook. México D.F.: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1982.

Coseriu, Eugenio. Introducción a la lingüística. Madrid: Editorial Gredos S.A., 1986.

De

la Torre, Giselle and Ferney Rodríguez. "Artificial intelligence: a new reasoning method for

legal science." Procedia Computer Science, no. 251 (2024): 801-13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2024.11.189.

Deutsch, David. La estructura de

la Realidad. Madrid: Editorial Anagrama S.A., 1999.

Díez, Cristian. "Voluntad y motivación en actos administrativos automatizados con

inteligencia artificial. ¿Un nuevo entendimiento de conceptos humanos?" InDret 4 (2024): 404-40.

Ester,

Antonio. "La inteligencia artificial en la justicia: desafíos y

oportunidades en la toma de decisiones judiciales." Anales de la Cátedra

Francisco Suárez, no. 59 (2025): 317-40. https://doi.org/10.30827/acfs.v59i.31404.

Fernández,

Francisco. "The future of court's procurators with the advent of artificial intelligence

technologies." Oñati Socio-Legal Series 14, no., 6 (2024): 1574-97. https://doi.org/10.35295/osls.iisl.1907.

García, Patricia. "Inteligencia artificial, predicciones y funciones normativas." Teoría y Realidad

Constitucional no. 54 (2024). https://doi.org/10.5944/trc.54.2024.43319.

Gómez,

Juan. "Inteligencia artificial y neuroderechos:

retos y perspectivas." Cuestiones Constitucionales 46 (2022): 93-119. https://doi.org/10.22201/iij.24484881e.2022.46.17049.

Harman, Gilbert. Significado

y existencia en la filosofía de Quine. México D.F.: UNAM, 1983.

Heidegger, Martin. El Ser y el Tiempo. México D.F.: Fondo de Cultura Económica

S.A., 2018.

Larenz, Karl. Metodología de la ciencia del Derecho. Barcelona: Ariel S.A., 1994.

León,

Jorge. "El tangram del Derecho: neguentropía y proceso jurídico." Novum

Jus 18, no.1 (2024): 127-54. https://doi.org/10.14718/NovumJus.2024.18.F5.

Marcus,

Solomon, Edmond Nicolau, and Sorin Stati. Introducción en la lingüística matemática. Barcelona: Editorial Teide S.A., 1978.

Mardones, J. M. Filosofía

de las ciencias humanas y sociales: materiales para unafundamentación. Barcelona: Editorial Anthropos S.A., 1991.

Martino, Antonio"The Digesto Jurídico Argentino: Considerations Concerning a Large Juridical Project." In Language,

Culture, Computation: Computing of the Humanities, Law, and

Narratives, edited by N. Dershowitz and E. Nissan, Lecture Notes in Computer

Science, vol. 8002. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer, 2014 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-45324-3_18.

Maza, Carlos. Aritmética

y representación: de la comprensión del texto al uso de materiales. Barcelona:

Paidós S.A., 1995.

Moreso, José Juan. "Las ficciones en Jeremy Bentham. El método de la Paráfrasis." Doxa: Cuadernos de Filosofía del

Derecho, no. 3 (1986): 129-39. https://doi.org/10.14198/DOXA1986.3.09.

Moreso, José Juan. Lógica, Argumentación e Interpretación en el Derecho. Barcelona:

Editorial UOC, 2004.

Otero, Milagros. "El

poder judicial frente al problema de la única respuesta correcta." Anales

De La Cátedra Francisco Suárez, no. 59 (2025): 405-26. https://doi.org/10.30827/acfs.v59i.30600.

Palau, Gladys. Introducción

Filosófica a las lógicas no clásicas. Barcelona: Editorial Gedisa S.A., 2002.

Peña, Jhonatan. "Inteligencia artificial para la

seguridad jurídica. Superando el problema de la cognoscibilidad del

derecho." Revista Oficial del Poder Judicial 14, no. 17 (2022): 55-117. https://doi.org/10.35292/ropj.v14i17.568.

Perelman, Chaim. El Imperio Retórico: Retórica y Argumentación. Bogotá

D.C.: Editorial Norma S.A., 1997.

Quattrocolo, Serena. "An introduction to AI and criminal justice." Revista Brasileira de Direito Processual Penal 5, no. 3 (2019): 1519-54. https://doi.org/10.22197/rbdpp.v5i3.290.

Ricoeur, Paul. Teoría de la Interpretación: Discurso y Excedente de Sentido. Madrid: Siglo XXI Editores S.A., 2006.

Ross, Alf. Lógica de las Normas. Madrid: Editorial Tecnos S.A., 1971.

Rovira, Joan, and Ana Gálvez. "Artificial intelligence and the production of judicial truth." Theory, Culture and Society 42, no. 1 (2025): 3-18. https://doi.org/10.1177/02632764241268174.

Rüdner, Richard. Filosofía de la ciencia social. Madrid: Alianza Editorial, 1973.

Schaff, Adam. Ensayos sobre filosofía del Lenguaje. Barcelona: Ed. Ariel S.A., 1973.

Segura, Estefanía. "Inteligencia artificial y administración de justicia: desafíos derivados del contexto latinoamericano." Revista de Bioética y Derecho 58 (2023): 45-72. https://doi.org/10.1344/rbd2023.58.40601.

Serrano,

José Luis. Validez y Vigencia: La aportación garantista a la teoría de la

Norma Jurídica. Madrid: Ed. Trotta S.A., 1999.

Stewart,

Ian. Conceptos de matemática moderna. Madrid: Alianza S.A., 1977.

Suarez,

Paulo. "Smartjustice, process and evidence:

special reference to its use in the court of appeal." Revista Brasileira de Direito Processual Penal 10, no. 2 (2024): 1-40. https://doi.org/10.22197/rbdpp.v10i2.1006.

Todorov,

Tzvetan, and Oswald Ducrot. Diccionario enciclopédico de las ciencias del

lenguaje. Madrid: Siglo veintiuno editores, 1998.

Von Kutzchera,

Franz. Fundamentos de

Ética. Madrid: Editorial Cátedra S.A., 1989.

White,

Douglas John. Teoría de la Decisión. Madrid: Alianza Editorial, 1972.

Wittgenstein, Ludwig. Tractatus Lógico-Philosophicus. Madrid: Alianza Editorial S.A., 1997.