|

|

ARTÍCULO DE INVESTIGACIÓN CIENTÍFICA, TECNOLÓGICA O INNOVACIÓN

The Aesthetics of the Social Rule of Law: The Case of Parque Biblioteca España in the City of Medellín*

La estética del Estado social de derecho: el caso del Parque Biblioteca España en la ciudad de Medellín

|

• Autor: istockphoto.com

|

10.14718/NovumJus.2023.17.2.15

Eduardo Andrés Perafán Del Campo**

* This article is the result of doctoral research to obtain the title of Doctor of Social Sciences from the University of Granada, in the research line Dynamics and changes in space and in the society of Globalization. This research has been tutored by Dr. Carmuca Gómez Bueno, to whom I express my sincere appreciation and feelings of gratitude for her time and dedication in guiding me in this doctoral adventure.

** PhD candidate in Social Sciences from the University of Granada, Spain. Master in political and international Studies and Political Scientist from Universidad del Rosario, Colombia. Director of International and Interinstitutional Affairs of Universidad del Quindío, researcher, academic editor, professor, analyst, and consultant in public and international affairs.

eduardoapdc@gmail.com

eduardoapdc@gmail.com

Received: April 1, 2023

Evaluated: May 15, 2023

Accepted: June 15, 2023

How to cite this article [Chicago]: Perafán Del Campo, Eduardo Andrés. "The Aesthetics of the Social Rule of Law: The Case of Parque Biblioteca España in the City of Medellín." NovumJus 17, no. 2 (2023): 375-402. https://doi.org/l0.14718/NovumJus.2023.17.2.15

Abstract

This article deepens and exemplifies the relationship between aesthetics, ideology, and politics by studying a case of aesthetic intervention in public space: the Parque Biblioteca España Project in Medellín, Colombia. In this way, from a qualitative methodological approach using mixed research instruments, this work will lead us to observe how the aesthetics of the Social State of Law was used as an aesthetic/political tool to confront social exclusion in Medellín.

Keywords: Aesthetics, Ideology, Politics, Public Space, Discourse, Medellin, Parque Biblioteca España,

Resumen

Este artículo profundiza y ejemplifica la relación entre estética, ideología y política por medio del estudio del caso de intervención estética en el espacio público: Proyecto Parque Biblioteca España en Medellín, Colombia. De esta manera, desde un enfoque metodológico cualitativo que utiliza instrumentos de investigación mixtos, este trabajo lleva a observar cómo la estética del Estado social de derecho fue utilizada como herramienta estético-política para enfrentar la exclusión social en Medellín.

Palabras clave: Estética, ideología, política, espacio público, discurso, Medellín, Parque Biblioteca España

Introduction

Aesthetics and politics are two categories relatively explored from different perspectives in the last decades. Thus, they range from critical or structuralist positions1,2 to those that delve into aesthetics as a discipline of the philosophy of art to nurture discussions on political art, architecture, or urban design3. However, although it is possible to identify literature on the subject, the horizon of research on the sensitive components and their relationship with the political, ideological, and discursive condition continues to be the subject of debate by a few researchers who have ventured to approach to their study from a contemporary perspective.

For this reason, due to the need to complement and enrich this debate, based on Perafán's doctoral studies, the article Ideology, Aesthetics, and Public Space4 was recently published, which was consolidated as a theoretical exercise to deepen some of the leading aesthetic/political debates developed in the literature and to establish an interdisciplinary discussion that would give meaning to the approach to sensitive objects of study from aesthetic, ideological and political categories.

In this order of ideas, from the advances of Perafán's doctoral thesis, of which this article is also a result, it has been possible to establish a way to materialize the study of sensitivity from political and ideological categories in a concrete object: public space. In this way, public space has emerged as a sensitive reality that can be accessed through an interdisciplinary approach in order to understand its ideological and discursive complexities, materialized in the sensitive elements that compose it.

In turn, by establishing a dialogue between the theoretical postulates of Bourdieu, Arendt, and Delgado, the public space manifests itself as a physical evidence of the result of the game of the political actors and the habitus of the dominant agents in the political held, a place of appearance that is also evidence of the rules of the game or moral and political conditions that would allow the emergence of concrete lines of political action, becoming both a product of the power games within the political field and a sensitive framework of the political.

Thus, after the publication of this article with a strong component of theoretical foundation, it is necessary to put these postulates into practice. Then, from the study of concrete aesthetic interventions in public space, it will be possible to observe how political discourses based on certain ideologies can be transformed into sensitive objects that condition the possible lines of political action staged in public space.

In this sense, this article is a research effort to deepen and exemplify the relationship between aesthetics and politics through the study of a case of aesthetic intervention in public space: the Parque Biblioteca España project in Medellín, Colombia. This research will lead us to observe how the ideology of social urbanism is transformed into a political discourse that, based on the aesthetics of the Social State of Law, becomes a sensitive object of representation of the State that conditions the lives of socially excluded populations.

Methodology

This article was based on a qualitative methodological approach, using mixed research instruments for the process of reviewing, systematizing, and analyzing documents, interviews, and graphic and audiovisual material, in order to reconstruct the political discourses and dominant ideologies representative of the professional elites that shaped the Biblioteca España project. At the same time, based on the process of observing the aesthetic characteristics of the graphic material rescued from the periods in which the Biblioteca España was used, a dialogue was established between the discourses, ideologies, and sensitive elements that allowed us to characterize this intervention in public space from an aesthetic/political perspective.

The contrast in the spring

In common Colombian slang, Medellín is known as the "city of eternal spring", and there are several reasons for this: The city's average temperature is 24 degrees Celsius throughout the year. It is culturally known for the Feria de las Flores, an annual event where hundreds of colorful flowers cover the city's streets. It is the epicenter of fashion, hosting Colombia Moda (Colombia's most influential fashion show), and it counts on a historic and well-known textile industry.5 Medellin is a vibrant city in the Aburrá Valley in the Cordillera Occidental (West Andes) of the Colombian Andes Mountains. Because of its unique geography, Medellín has an irregular topography that is now part of its identity as a city of the mountains. The Medellín River, which flows through the city from south to north, has become a referent for urban planning. Medellin is divided into 16 comunas [communes] and 249 neighborhoods.

The capital of the department of Antioquia, Medellin, is one of the wealthiest regions in Colombia. It produces 14,5 % of Colombia's GDP.6 This percentage is only surpassed by the city of Bogota (the capital of Colombia). In terms of population, the capital of Antioquia is the second-largest city in Colombia, with almost 2,533,424 people in 2020. In recent years, Medellin has experienced a significant economic development thanks to a substantial industrial growth, positioning itself internationally as a city of innovation that has creatively faced its main social challenges. In 2013, Medellin was named the most innovative city in the world among 200 cities by the Wall Street Journal magazine and the Citi Group. In 2019, due to the innovative dynamics developed in the city, Medellin was chosen as the center of the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

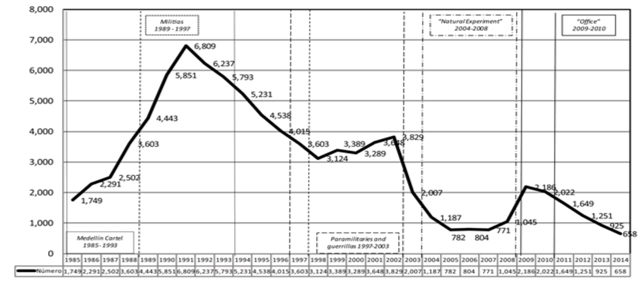

However, this city, which today is projected as a national and international example of innovation and social policy, went through a brutal period in which violence was widely disseminated through all mass media. Reports from the 90s showed how relentless violence covered the streets of Medellin.7 They witnessed the convergence of multiple illegal actors, who, empowered by inequality and poverty, occupied the space of the city. Medellin was the epicenter of paramilitary violence, urban guerrilla confrontation, and the emergence of one of the most violent drug cartels in the country's history.8 The following graphic shows that Medellin reached historic levels of violence in 1991. With more than 6809 murders per hundred thousand inhabitants, the city attained the highest homicide rate in the world that year.9

However, at the turn of the 21st century, an accelerated decline in violence rates was perceived. The academic community has studied such a phenomenon. This condition can be observed in the following graph, which shows the homicide until 2015. This graph has been deliberately chosen with data only up to that year since, as explained below, it corresponds to the temporary closure of the Biblioteca España.

Figure 1. Temporary closure of the Biblioteca España

Source: Taken from J. Giraldo-Ramírez and A. Preciado-Restrepo, "Medellín,

from Theater of War to Security Laboratory,"

Stability: International Journal of Security & Development (2015): 3.

Poverty and exclusion in Medellin: the aesthetics of ghettos and communes

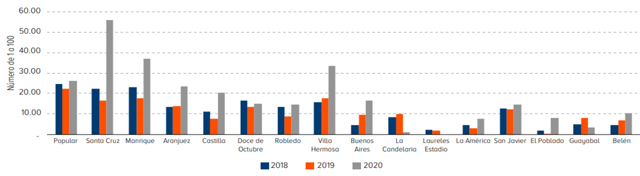

The population of the Antioquian capital comprises 43% of the middle-class, 32,9% poor and 20,5% vulnerable population, and 3,6% upper class.10 Of course, these numbers are conditioned by the strong impact of the pandemic that drastically affected economic conditions, so it would be pertinent to bring the data for 2018 to have a vision of the pre-pandemic context. For 2018, 65,8% of the population was middle class, 10,7% upper class, 4,2% poor, and 19,4% vulnerable.11 In this sense, it is possible to observe that most people are in the middle-class range, established in the city's economic and social context. However, almost a quarter of the population is vulnerable and lives below the poverty line. This implies that, considering the number of inhabitants in 2020, almost 600,000 are in the latter condition. A not insignificant number at all. In addition, Medellin stood out as a highly unequal city in 2020, with a Gini index 0,56.12 On the other hand, the urban geography of Medellín allows us to observe the poverty concentrations in the communes, in areas where the topographical conditions are not suitable for living.

Generally, communes are located on landslide-prone hillsides, and most houses are improvised, informal structures built by a high percentage of communities displaced by the armed conflict that Colombia has experienced. Such houses increase the vulnerability of these communities to natural disasters.13 These informally urbanized areas have become hyperghettos following their establishment and urban densifi-cation. In the context of contemporary society, the academic Zygmunt Bauman,14 citing Wacquant,15 defined a hyper ghetto as: "a one-dimensional mechanism of pure relegation, a human camp where those segments of urban society are discarded, which appears embarrassing, worthless, and dangerous". In turn, such places become scenarios of social stigmatization, where "the stigmatized person is considered disqualified for full social acceptance due to some socially sanctioned defect, flaw or disadvantage".16 In this sense, the social and relegated communes were built as recipients of the socially and economically unstable population. They were transformed into proscribed places, socially undesirable scenarios where social micro-orders17 were constituted parallel to the State, disconnected from the city, and became epicenters of the violence that consumed the city in the 1990s.

Figure 2. Map of Medellín

Source: Taken from O. P. Plata,

"Externalidades ambientales ocasionadas por la urbanización en la ciudad de Medellín,"

Procesos Urbanos 3 (2016): 38-54.

Figure 3. Multidimensional Index of Living Conditions in Medellín (IMCV)

Source: Taken from Medellín cómo vamos, 12 June, 2019,

https://www.medellincomovamos.org/la-ciudad/

The graphs above show the spatial distribution of the city and the Multidimensional Index of Living Conditions (IMCV) differentiated by communes with a higher IMCV and those with a lower IMCV. In this way, we can observe that the communes of the northeast region have the lowest indexes in living conditions and share the characteristics described above in terms of complex topography and informal settlements at high geographical risk. However, it is essential to highlight that the living conditions of the population in these communes (northeast) have improved significantly since the beginning of the XXI century due to the implementation of social programs, investments in infrastructure and the improvement of public spaces by the local government. Although these communes are still impoverished, their reality has changed dramatically compared to the 90s, especially in terms of reducing violence and improving living conditions.18

Aesthetics revolution and social urbanism

On October 26, 2003, the candidate of an alternative political party, Sergio Fajardo Valderrama, won the mayoral election of Medellín. In 2014, the beginning of his administration would define a new approach to public policy that would determine the responses from the municipal government to the main problems facing Medellín: Poverty, inequality, and violence. Within such an approach, the aesthetics of public space would become relevant. Many interventions would begin, which today are consolidated as important references at the national and international levels concerning public space management.

Medellin, once the epicenter of drug narcotrafficking, has now consolidated itself as an important and successful example of innovation in space management linked to social policy. The "Medellín model" has begun to be studied and acknowledged by the international community and replicated in other cities worldwide. Holmes and Gutiérrez highlight:

In 2009 the foundation that runs the Medellín library system, the EPM Foundation, received a US $1.000.000 Access to Learning Award from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. In 2010, three programs were recognized as best practices by UN-Habitat: Medellín Solidaria [Medellin solidarity], which has improved the quality of life of 45,000 of the poorest households (in terms of income, education, health, nutrition, housing, access to credit, justice, etc.); Programa Buen Comienzo [Getting Started Program], which has provided comprehensive developmental services to children from birth to age five since 2006; and the city's Encuesta de Calidad de Vida [Quality of Life Survey]. In January 2012, the city was awarded the Sustainable Transport Award from the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy (ITDP) for the Metrocable, which connects some of the city's peripheral neighborhoods to the metro.19

Thus, the recognition of such a model positioned Medellin as a city of the vanguard. However, the question remains: What did the Medellin model consist of? Capillé20 answers this question as follows: "The 'Medellín Model' can be synthesized as the explicit associations between environments that were once poor and violent, and those that have become 'smart', 'innovative' and 'upgraded" through a series of urban transformations of governance and infrastructure. In this model, aesthetics plays a fundamental role as the design of such interventions would be established as the primary vehicle for the symbolic production of new meeting spaces and the construction of new urban identities. In this context, as Mazzanti21, the architect in charge of the iconic transformations of Medellin's public space, has expressed, architecture has been established as the government's response to Medellin's social transformation into a less violent and more egalitarian city.

Let us recall that, based on the theoretical development of Perafán,

Public space is also the scenario where political action takes place. From Hannah Arendt's perspective, such action is consolidated as the physical manifestation of freedom, which requires the crystallization of a set of moral and political conditions (Díaz: 2013). In this sense, such conditions appear in the public space as enabling and conditioning elements of political action, either from the Arendtian democratic perspective or from axiological referents that are far from democracy (totalitarianism, despotism, etc.). The moral condition in the public space refers to the evidence of values, principles, and ideas that constitute the axiological framework of interaction in the public space. On the other hand, the political condition mentioned by Arendt could refer to the power relations that condition the possibility of appearance or invisibility of certain actors, ideas, and manifestations in the public space. [...]

Based on the previously developed approaches, aesthetic intervention in public space could condition how political action emerges. This means that if the values shared by the professional elites and imprinted in the aesthetics of public space are oriented to "establish relationships between people belonging to a diverse and plural community that seeks to maintain a certain sense of community" (Díaz: 2013, p. 942) and to strengthen community ties through respect and recognition of differences, we could observe a space that consolidates itself as a fertile ground for democratic political action. In this sense, aesthetics becomes a fundamental tool for shaping a concrete political project that can lead to more or less democratic social realities.22

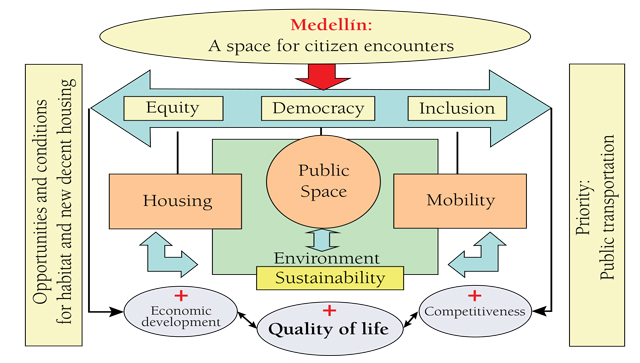

Therefore, based on our object of study, the 'Medellin model' was based on the city's 2014 Plan de Desarrollo [Development Plan], which was the integrating document of Medellin's public policies for the next four years. In this plan, we can see how the notion of democracy is linked to the idea of public space. In this sense, on the basis of this document, democracy was conceived as a reality that would be achieved through the materialization of specific values in the public space, which, hand in hand with Arendt's theory, would be fundamentally consolidated as a space for citizen encounters. See the following graphic, taken from the Development Plan ofMedellfn for 2004.

Figure 4. Axis 3: Medellín: A space for citizen encounters

Source: Taken from Alcaldía de Medellín,

Plan de Desarrollo de Medellín: "Medellín, compromiso de toda la ciudadanía" (2004).

This development plan consolidated the public space as a democratic catalyst. It is the place where all urban activities converge and where the city's political projects are carried out. It is essential to highlight that the government's efforts were concentrated in places with higher indices of inequality and violence. In this sense, most of these interventions have taken place in the most backward communes of Medellin, disconnected peri-urban areas that have not participated in urban, social, and economic development. In this way, the creation of meeting spaces in these territories raises the possibility of recovering the social fabric and including invisible populations in the development process. Reshaping these territories with the city by improving mobility infrastructure, promoting inclusion, and providing access to quality housing and the enjoyment of essential public services would allow for greater equity. This would lead to civic empowerment of the left-behind sectors, which could encourage economic development, competitiveness and quality of life in these areas.

Capillé synthesizes the materialization of these strategies through the following achievements:

Among the main strategies used in the project of 'urban and social upgrading' in Medellin, one can include: firstly, a transport strategy, with the implementation of the 'Metrocables' (aerial cableways), which enabled access to the main metro line to the population of underprivileged areas of the city. Secondly, the construction of social housing projects in the same neighborhoods. Thirdly, the construction of public libraries of 'great architectural impact' (namely the Library-Parks Project), which offered a wide range of services to the surrounding communities. Fourthly, the Urban Improvement Program included the renovation of schools and other public facilities. The fifth and last strategy refers to the renovation of urban public spaces, connecting all projects to show the integration of investments.23

The above-mentioned strategies revolved around a discourse that, together with the Medellin model, would be one of the main elements through which the capital of Antioquia would be internationally recognized: social urbanism [US, for its Spanish acronym]. For this reason, this concept will demand our attention in the following pages. According to Montoya:

Only the law and its legitimate discourse facilitate the affirmation that a physical transformation -the construction of a library, for example- is social urbanism. Thus, the US social adjective does not describe or explain an exercise in planning, organization, or territory management; it justifies it by creating the conditions of possibility for its exercise.24

Social Urbanism, more than a model of urbanism, was the discursive practice that allowed the incursion of the State into the local reality of Medellin. A State that, until recently, had been termed the "Social Rule of Law" and had remained distant from local realities, conditioned by shared perceptions regarding state impunity,25 controversial responses of the legal system such as penal populism26 and selective justice,27 whose absence exacerbated social inequalities and violence. Social Urbanism was the discourse that legitimized the appearance of the Social Rule of Law in the public space of Medellín, from the new principles of territorial decentralization and the construction of policies thought on local realities, introduced in the Political Constitution of 1991. In this sense, in a space co-opted by illegal actors and whose moral and political conditions hardly allowed the emergence of democratic political action, a new actor that reconsidered the possibilities of appearance and visibility in public space came to light. Said actor was the State, whose aesthetic representation was manifested through interventions in public space, an architecture of symbols of the Social Rule of Law.

The construction of new transportation systems that shortened the physical and social distance between peri-urban territories and developed urban centers, the provision of educational and health infrastructure in depressed neighborhoods, and the creation of new spaces that allowed for encounters and recreation among citizens in vulnerable conditions were examples of the construction of symbols in public space conceived as stages of a new citizenship. According to various interventions by Sergio Fajardo, citizenship would integrate the principles of tolerance, respect, and the disarticulation of violence as a form of social interaction. In this sense, these new intervened spaces would be theaters where the relationships staged in them would allow the reconstruction of the social fabric and project a new image of the city, which would not only be attractive and a source of pride for its citizens, but also a powerful pole of attraction for investment. In this way, social urban planning would promote social development and economic competitiveness in the city.

On the other hand, according to Montoya, if we think about social urbanism from an ideological condition, we could point out that:

The US [(social urbanism)], as an ideology, plays equally with enjoyment, pleasure, and scarcity (Gunder 2010: 305), thus carrying out an operation that , as a display of power, builds and establishes a set of needs with the aim of achieving a representation in people that allows for political identification with the US, a term that also denotes a model that guarantees both governability and governance strategies. [...] In this specific case, the effect of producing subjectivities, creating a set of needs, and then satisfying them is of particular interest. Given that the US is the strategy of the public function of urban planning in the city of Medellin, it must be affirmed that the main tools used as ideology are the rights of the inhabitants of Medellín, especially their collective rights.28

Along these lines, the ideology that crystallized in the discourse of social urbanism in Medellín referred to a set of ideas and beliefs shared by the professional elites that governed Medellín during 2004-2011. If we recall the proposals of Bourdieu,29 Hannah Arendt,30 and Delgado,31 we could think that these professional elites, whose visible heads were the mayors Sergio Fajardo and Alonso Salazar, and whose social vision of Medellín was validated by the elections that made them winners, wanted to make public space a place for the staging of citizens' rights, rights that had been decimated by the inequality, violence, and, in particular, social actions of criminal relevance,32 that had robbed the possibility of the appearance of democratic political action in public spaces.

Following Perafán's statements, it should be recalled that:

Part of the exercise of control over the form of public space by certain professional elites lies precisely in the possibility of exercising control over the state that this common appearance acquires. It is the form through which the internalization of certain aspects is sought as principles of identity and axiological referents of civic action. The political game behind the decision-making process regarding urban morphology could be translated into a search for the positioning of an aesthetic of what can be seen, felt, and heard by citizens in public space. In the face of this, as in any political process, there would be a differential appropriation by those interacting with and in public space. We could observe the emergence of agreements and disagreements, strategies of resistance, and the clarification of different ways of thinking, feeling, and living in this space.33

Thus, wide social gaps, evident in the aesthetics of ugliness attributed to the slums, which referred to feelings of mistrust and insecurity, and the invisibility of the ghettos due to the physical disarticulation of the hillsides with the developed centers of the city, were confronted by the beautihcation of the peri-urban centers, the arrival of a new architecture that represented the social function of the State and the embellishment of the lifestyles of those who lived there. In this way, these places, once condemned to be the dumps of everything socially proscribed, became the main focus of intervention of an aesthetic revolution that revitalized and made visible the urban ghettos, transforming them into new spaces for meeting, "participation, [...] promotion of coexistence and respect for life".34 This aesthetic revolution resulted from a new urban morphology based on the ideology and discourse of social urbanism. A process of the aestheticization of politics, which aimed at printing in the public space the enabling values of democratic political action and to erect symbols of the Social Rule of Law as sensitive objects that would be integrated into the everyday architecture and the identity of the citizens who would interact with them.

Library Parks: the Biblioteca España project

On March 22, 2007, one of the most representative icons of Medellin's urban transformation, Parque Biblioteca España, was inaugurated in a solemn ceremony. This ceremony took place in the library's facilities, located in the Santo Domingo Savio neighborhood, surrounded by the "comunas" of La Popular and Santa Cruz, formerly one of the areas with the highest rates of inequality and violence in the city. This event, held in an area that has been difficult to access in terms of both security and mobility, was attended by various political personalities such as the President of the Republic of Colombia, ministers of the National Government, community leaders, and two special guests: the King and Queen of Spain.

The ceremony was presided over by the mayor of Medellín, Sergio Fajardo Valderrama, who gave an official speech in which he highlighted some of the ideas already expressed in other media and included in the 2004 Development Plan for Medellin. Thus, Sergio Fajardo began his intervention with a reflection on the place where the attendees were, highlighting the almost implausible nature of the reason that brought them together:

Now, let us think about where we are. You can look over there (La Popular and Santa Cruz colonies) and see some houses attached to the mountain. Incredible places where no one could imagine that in Santo Domingo Savio we could have all this amount of people sharing a common space.35

In this way, this historically isolated and invisible area became the meeting point of outstanding political personalities who came together to create a new symbol that represented the crystallization of social urbanism. In his speech, the mayor explicitly mentioned the symbolic nature of the library: "We are building the symbols of this Medellín that is being transformed [...] a beautiful, majestic, perfectly designed building appears, which is a symbol of this new city [...] The dream of dignity, opportunity, justice and equality, so that we can all be free".36 In this sense, the Biblioteca España [Spain Library] symbolizes the government's efforts to create new public spaces where meetings and the rejection of violence as a social practice are possible. Let us remember that, for Hannah Arendt,37 democratic political action is not possible in violent contexts, and it is only in settings where freedom exists as a fundamental condition that democratic political action is fertilized. Therefore, in Fajardo's speech and in his emphasis on the possibility of achieving freedom through this type of intervention, he is referring precisely to said Arendtian principle.

The Biblioteca España [Spain Library], currently closed to the public and in a state of revitalization and structural readjustment due to defects in its facade in 2015, was developed as part of the project to build a network of library parks in Medellín. This project was articulated with the discourse of social urbanism, in which libraries would not exclusively fulfill a traditional function of a librarian character, because in addition to books, magazines, and films, they would make computers with free Internet access and a broad cultural agenda available to citizens. This strategy of approaching the general public through the more playful side of culture is working in Medellín. On the other hand, the name "parks" would refer to the public and to the conditions of encounter that, through their architecture, would allow them to be consolidates as new physical frameworks for the construction of a new citizenship, where the values contained in the social urbanism discourse of professional political elites would come to life.

Regarding the role of library parks in the materialization of social urbanism in public spaces, Capillé points out:

The Library-Parks of Medellín are pivotal in this city's urban and social upgrading project. They consist of a combination of cultural programs and generous outdoor and indoor spaces for public use, built to produce a new sense of community and citizenship through architecture and its appropriation [...] Among all the urban upgrading projects, the Library-Parks occupy a critical position, as they become the architectural manifestation of top-down ideological propaganda and the possibility of everyday community engagement. [....] Firstly, to use architecture to represent an 'upgraded' society; and secondly, to 'produce' social change through the arrangement of spaces that can generate a new sense of community and citizenship through informal co-inhabitation and interaction.38

Thus, the social function that the Biblioteca España Park would fulfill would be crucial to the fulfillment of the objectives of the Medellin government. This can be seen, for example, in the determination of a faction of the city's political actors to build said library in a territory that, under expert judgment, represented a challenge of unprecedented magnitude. As the geologist Nora Cadavid pointed out in an interview for one of the State's communication channels, the land on which the library was to be built "is the worst place in terms of the geological offer, but the social and political impact of the building is higher".39

From an aesthetic perspective, as Capillé40 notes, in the case of Biblioteca España, the architecture of this type of intervention shared two conditions: contrast and monumentality. This work of architecture, winner of the Sixth Ibero-American Biennial of Architecture and the only work of Colombian architecture exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, is erected with a clear contrast between its contemporary design and modern facilities and the local and precarious architecture of the surrounding buildings. The library breaks the horizon and rises defiantly on the Santo Domingo hill, establishing itself as a disruptive visual reference for those who, from any angle, set their sights on the neighborhoods of La Popular and Santa Cruz.

Figure 5. The library on the Santo Domingo hill

Source: Taken from S. Gómez S, Archdaily, 19 February,

https://www.archdaily.co/co/02-6075/biblioteca-parque-espana-giancarlo-mazzanti

Although the library design is perceived as alien to the disorganized aesthetics of the neighborhood, with its irregular facades and mainly invading dwellings, the library starts from a syncretism with the mountain. As Giancarlo Manzzati, the library's architect, points out, Medellín has a mountainous geography that makes it unique and constitutes its territorial aesthetics. This building "is born from the earth, belongs to the geography, and is built as part of that geography"41. In this way, the library façade's sections, color, and texture resemble the rocks that are part of the mountainous landscape. However, the syncretism with the terrain differs from the obvious contrast with the human settlements in the mountains. In this sense, we could think that this contrast is assumed in a premeditated way by the professional elites in this intervention and not as an unexpected result after the library's construction.

Figure 6. Library architecture between mountains and neighborhoods

Source: taken fromj. Gobbi, Flickr, 31 October,

https://www.flickr.com/photos/momssey/10965261034

In this case, contrast is the aesthetic tool through which the creation of a new public space was symbolized. Different from the dynamics of inequality, exclusion, and violence that preceded life in the La Popular and Santa Cruz communes and that were rooted in the aesthetics of marginal neighborhoods, the possibility of a new form of human interaction is proposed within the framework of a new aesthetic.

As Manzzati42points out, the aesthetic challenge of the library lay in "how we fostered a different way of life and how we promoted it in purely visual terms". This different way of living is the one that favored encounter as the fundamental basis of the public space, which assumed a physical framework that stood symbolically as a place endowed with beauty in a context devoid of it, and through which those who had been marginalized and invisible, would also be able to claim their possibility of access to beauty. This idea can be extracted from one of Sergio Fajardo's pronouncements regarding this project: "We are going to break with the idea that the most beautiful things are for the richest, but that the most beautiful things are for the humblest".43

In this order of ideas, although the explicit objective of this type of intervention was to promote social inclusion, the contrast was established as a mechanism of differentiation between a way of life that did not allow the emergence of democratic political action and a new form of life that was within the reach of the inhabitants of the commune: physically located a few meters from the reality of the ghetto, it would be enough to look at the façade or to go to the library facilities to symbolically place oneself in a different reality. In this sense, paradoxically, the inclusion started from the idea of the exclusion of the neighborhood's aesthetics that was built locally. For this reason, the incursion of this new aesthetic, to a certain extent perceived as alien, provoked resistance from the inhabitants of the surrounding neighborhoods. Some of them chained themselves to the construction site to prevent the work from developing. However, it is understandable that an intervention of this magnitude, in the context of populations historically neglected by the State, could generate uncertainty by introducing new rules of the game within the neighborhood.

Figure 7. Incursion of new aesthetics

Source: Taken from Dthebault, 2013, Biblioteca España, Medellín, Beautifullibraries.wordpress.com, Octubre. https://beautifullibraries.wordpress.com/2013/10/10/biblioteca-espana-medellin/

On the other hand, the monumentality observed in this intervention refers to the State symbolism of the sublime, typical of the processes of the aestheticization of politics that seek to represent the power of the State in public space44. In this way, the sublime is always gigantic. It shakes, astonishes, and can evoke widespread feelings of terror or well-being in contemplation45. The sublime reminds the viewer of his hniteness, his limitations, and the existence of something infinitely superior to him46. Thus, the aesthetics of the Biblioteca España is also the aesthetics of the resounding irruption of the State in a territory whose figure and power had been blurred.

In the hrst instance, in the face of violence and the cooptation of public space by illegal actors who challenged the Weberian maxim47 of the legitimate monopoly of force by the State, the colossal figure of the State appears, recalling the Rule of Law in the communes. Secondly, in the face of the social demands of an underprivileged population and its disarticulation from the rest of the city, the social function of the State is symbolized, creating a new meeting place and promoting social programs to improve the quality of life of its habitants. In this sense, the aesthetics of the sublime, on which the library is erected, proposes and symbolizes the updating of the social contract, through which the inhabitants of the communes La Popular and Santa Cruz are reminded that the State exists in their territory, that they are subordinate to it, and that only through it they can achieve their fulfillment as full citizens.

Now, after reflecting on the aesthetics of contrast and the sublime in the Biblioteca España, we could initially explore some indicators of the expected results of this intervention by the government of the city of Medellín. Although, as we have already indicated, in this article we will not delve into the process of differential appropriation by the inhabitants of the territory where the library was located, we will refer to the study carried out by Holmes and Gutierréz48 regarding the measurement of the immediate impact of this intervention.

These authors collected and analyzed the district survey results measuring the quality of life in the city of Medellín in the years 2008, 2009, 2010, and 2011. When comparing the results of the inhabitants of the area where the Biblioteca España intervention took place, it was possible to identify that they had a better evaluation than the rest of the city regarding: a) satisfaction with Medellín as a city to live in b) citizen responsibility c) respect for basic rules of coexistence d) respect for life e) perception of security f) crime and g) trust in the police.

Faced with these results, Holmes and Gutierrez mentioned:

Although these public spaces are highly valued throughout the city, there was an even higher perception of civic responsibility toward public spaces such as libraries and parks in Popular and Santa Cruz. [...] Popular and Santa Cruz residents also report higher compliance with and respect for basic rules of civility in the year the library opened. [They also] report a higher respect for life in 2007 in Popular and Santa Cruz than in Medellín. [.] These surveys reveal an optimism and satisfaction with life that may surprise some, given the community's violent past and relative poverty. [Moreover, the] level of perceived security is higher than in the city as a whole [and] there appears to be little crime in Popular and Santa Cruz. In fact, in May 2010, the authors were able to walk around the neighborhood without escort or concern. The plazas were filled with children playing and others enjoying the spaces49.

In this order of ideas, although it is necessary to delve into other types of variables to measure the socio-economic impact of the Biblioteca España project, it is possible to identify that there was a separate positive response from the community, linked to its representation towards the city, in the four years after its construction. In this sense, we could think that the emergence of the Social State of Law from the narrative of social urbanism and its manifestation through the architecture of the Biblioteca España conditioned the sensitive frames of reference of the population. The degree of this conditioning, the processes of differential appropriation of symbols in the public space, and the various studies that can emerge from their research will be the subject of other research that can enrich the literature on the subject. Let us recall that the efforts we have made so far in this work have been aimed at reconstructing a process of aestheticization of politics and showing how aesthetics and politics combine in the public space to produce powerful symbols that condition the lives of citizens.

Conclusions

The Parque Biblioteca España project in Medellín was based on the discourse and ideology of social urbanism, which justified the creation of new meeting spaces to improve the quality of life of the most vulnerable populations and reduce the effective rates of violence. The Biblioteca España [Spain Library] was erected as a symbol of the social function of the State, which broke with the logic of State abandonment of the La Popular and Santa Clara communes. The library made visible a proscribed, invisible, and disarticulated territory from the rest of the city. This intervention started from the aesthetics of contrast and the sublime to symbolize the creation of a new space that opened the doors to a new way of life and the establishment of the State's image in the community's aesthetics. This library rose above the urban landscape to become a symbol of a new city, a new citizenship, and the reestablishment of the social contract that would protect the less privileged populations. Finally, it is essential to call upon the government of the city of Medellín to guarantee the prompt awarding of the contract for the restoration of the library and the start and completion of the works that must be carried out in order for the Parque Biblioteca España to function properly again.

Notes

1 Eduardo Andrés Perafán Del Campo, Sebastián Polo Alvis and Jessica Lizeth Caro Pulido, "Mirror box: ¿una reivindicación estética sobre el capital erótico de la mujer?," Revista Latinoamericana de Sociología Jurídica 1, no. 1 (2020): 189.

2 Eduardo Andrés Perafán Del Campo, "La desigualdad como experiencia estética: una corta reflexión

para la sociología jurídica y política," Novum Jus 13, no. 1

(2019): 7-10.

3 Eduardo Andrés Perafán Del Campo, "Estética, ideología y espacio público," Utopía y Praxis Latinoamericana 24, no. 4 (2020): 68-72.

4 Eduardo Andrés Perafán Del Campo, "Estética, ideología y espacio público," Utopía y Praxis Latinoamericana 24, no. 4 (2020): 65-83.

5 Medellín cómo Vamos, 12 June, 2021. https://www.medellincomovamos.org/node/18687

6 Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística (DANE), Resultados PIB departamental 2022 preliminar (Base 2015) (Bogotá: DANE, 2022).

7 Andrés Eduardo Fernández Osorio and Yerlin Ximena Lizarazo-Ospina, "Crimen organizado y derechos humanos en Colombia: enfoques en el marco de la implementación del Acuerdo de Paz con las Farc-Ep," Novum Jus 16, no. 2 (2022): 223.

8 Jennifer S. Holmes and Sheila Amin Gutiérrez de Piñeres, "Medellín's Biblioteca España: Progress in unlikely places," Stability: International Journal of Security & Development 3, no. 1 (2013).

9 Jorge Giraldo-Ramírez and Andrés Preciado-Restrepo, "Medellín, from Theater of War to Security Laboratory," Stability: International Journal of Security & Development 4, no. 1 (2015): 1-14.

10 Medellín Cómo Vamos, Informe de Calidad de Vida de Medellín, Medellín: Medellín Cómo Vamos, 2021.

11 Medellín Cómo Vamos, Informe de Calidad de Vida de Medellín, Medellín: Medellín Cómo Vamos, 2019.

12 Medellín Cómo Vamos, Informe de Calidad de Vida de Medellín, Medellín: Medellín Cómo Vamos, 2021

13 Juan Ignacio Toro, Carlos Vásquez Higuita, Mario Sánchez Vásquez, Esteban Mesa Toro and Elkin Vargas González, "Santo Domingo Savio: un territorio reterritorializado," Territorios 22 (2010): 73-88.

14 Zygmunt Bauman, Vidas desperdiciadas: la modernidad y sus parias (Barcelona: Paidós, 2004).

15 Loïc Wacquant, "Urban outcasts: stigma and division in the black American ghetto and French urban periphery," International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 15, no. 3 (1993): 365-372.

16 Pablo Elías González Monguí, Germán Silva García, Angélica Vizcaíno Solano, "Estigmatización y criminalidad contra defensores de derechos humanos y líderes sociales en Colombia," Revista Científica General José María Córdova 20, núm. 37 (2022): 146-147.

17 Germán Silva García, "¿El derecho es puro cuento? Análisis crítico de la sociología jurídica integral," Novum Jus 16, no. 2 (2022): 63.

18 Juan Ignacio Toro, Carlos Vásquez Higuita, Mario Sánchez Vásquez, Esteban Mesa Toro and Elkin Vargas González, "Santo Domingo Savio: un territorio reterritorializado," Territorios 22 (2010): 73-88.

19 Jennifer S. Holmes and Sheila Amin Gutiérrez de Piñeres, "Medellín's Biblioteca España: Progress in unlikely places," Stability: International Journal of Security & Development 3, no. 1 (2013): 2.

20 Carlos Capillé, "Political theatres in the urban periphery: Medellin and the library-parks project," Bitacora 28 (2018): 127.

21 Giancarlo Mazzanti, "La identidad latinoamericana no se da a través del lenguaje arquitectónico," ArchDaily, April 2015. https://www.archdaily.co/co/765822/entrevista-giancarlo-mazzanti

22 Eduardo Andrés Perafán Del Campo, "Estética, ideología y espacio público," Utopía y praxis latinoamericana 24, núm. 4 (2020): 74.

23 Carlos Capillé, "Political theatres in the urban periphery: Medellin and the library-parks project," Bitacora 28 (2018): 128.

24 Natalia Montoya Restrepo, "Urbanismo social en Medellín: una aproximación a partir de la utilización estratégica de los derechos," Revista Estudios Políticos 45 (2014): 214.

25 Germán Silva García, "La construcción social de la realidad. Las ficciones del discurso sobre la impunidad y sus funciones sociales," Via Inveniendi et Iudicandi 17, núm. 1 (2022): 105-123.

26 Germán Silva García y Vannia Ávila Cano, "Control penal y género ¡Baracunátana! Una elegía al poder sobre la rebeldía," Revista Criminalidad 64, núm. 2 (2022): 31.

27 Germán Silva García y Johana Barreto Montoya, "Avatares de la criminalidad de cuellos blanco transnacional," Revista Científica Generaljosé María Córdova 20, núm. 39 (2022): 615-616.

28 Natalia Montoya Restrepo, "Urbanismo social en Medellín: una aproximación a partir de la utilización estratégica de los derechos," Revista Estudios Políticos 45 (2014): 217.

29 Pierre Bourdieu, Sociología y cultura (Ciudad de México: Grijalbo, 1990).

30 Hanna Arendt, Qué es la política (Barcelona: Paidós, 1977).

31 Manuel Delgado, El espacio público como ideología (Madrid: Los Libros de la Catarata, 2015).

32 Germán Silva García, Fabiana Irala y Bernardo Pérez Salazar, "Das distorções da criminologia do Norte global a uma nova cosmovisão na criminologia do Sul," Dilemas 15, núm. 1 (2022): 188.

33 Eduardo Andrés Perafán Del Campo, "Estética, ideología y espacio público," Utopía y Praxis Latinoamericana 24, no. 4 (2020): 75.

34 Natalia Montoya Restrepo, "Urbanismo social en Medellín: una aproximación a partir de la utilización estratégica de los derechos," Revista Estudios Políticos 45 (2014): 216.

35 Sergio Fajardo, "Discurso de Sergio Fajardo en la inauguración del Parque Biblioteca España," YouTube, March 13, 2007, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SGwJxM26BV0&t=1s.

36 Sergio Fajardo, "Discurso de Sergio Fajardo en la inauguración del Parque Biblioteca España," YouTube, March 13, 2007, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SGwJxM26BV0&t=1s.

37 Hanna Arendt, ¿Qué es la política? (Barcelona: Paidós, 1977).

38 Carlos Capillé, "Political theatres in the urban periphery: Medellin and the library-parks project". Bitacora 28 (2018): 129-130.

39 Señal Colombia, "Maravillas de Colombia: Biblioteca España, Medellín," YouTube, 4 August, 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pft1So0oVls

40 Carlos Capillé,

"Political theatres in the urban periphery: Medellin and the library-parks

project", Bitacora 28 (2018): 128.

41 Giancarlo Mazzanti, "La identidad latinoamericana no se da a través del lenguaje arquitectónico," ArchDaily, April 2015, https://www.archdaily.co/co/765822/entrevista-giancarlo-mazzanti

42 Señal Colombia, "Maravillas de Colombia: Biblioteca España, Medellín," YouTube, 4 August, 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pft1So0oVls

43 Señal Colombia, "Maravillas de Colombia: Biblioteca España, Medellín," YouTube, 4 August, 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pft1So0oVls

44 Benjamin, Walter, La obra de arte en la época de la reproductibilidad técnica (Madrid: Taurus, 1982).

45 Kant,

Immanuel. Observaciones

sobre el sentimiento de lo bello y lo sublime (Buenos

Aires: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2004).

46 Scheck, David O., "Lo sublime y la reunificación del sujeto a partir

del sentimiento: La estética más allá de las restricciones de lo bello," Signos

Filosóficos 15 (2013): 103-135.

47 Weber, Max, Economía y sociedad: esbozo de

sociología comprensiva (México: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1964/1922).

48 Jennifer

S. Holmes and Sheila Amin Gutiérrez de Piñeres, "Medellín's Biblioteca

España: Progress in unlikely places," Stability: International Journal

of Security & Development 3, no. 1 (2013).

49 Jennifer

S. Holmes and Sheila Amin Gutiérrez de Piñeres,

"Medellín's Biblioteca España: Progress in unlikely places".

References

Alcaldía de Medellín. Plan de Desarrollo de Medellín: Medellín, compromiso de toda la ciudadanía. Medellín, 2004.

Amézquita-Quintana, Claudia. "Los campos político y jurídico en perspectiva comparada. Una aproximación desde la propuesta de Pierre Bourdieu." Universitas Humanística 65 (2008): 89-115.

Arendt, Hannah. ¿Qué es ¡apolítica?Barcelona: Paidós, 1977.

Bauman, Zygmunt. Vidas desperdiciadas: la modernidad y sus parias. Barcelona: Paidós, 2004.

Benjamin, Walter. Estéticaypolítica. Buenos Aires: Las Cuarenta, 2009.

Benjamin, Walter. La obra de arte en la época de la reproductibilidad técnica. Madrid: Taurus, 1982.

Bourdieu, Pierre. Sociología y Cultura. Ciudad de México: Grijalbo, 1990.

Capillé, Carlos. "Political theatres in the urban periphery: Medellin and the library-parks project." Bitacora 28 (2018): 125-134.

Delgado, Manuel. El espacio público como ideología. Madrid: Los Libros de la Catarata, 2015.

Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística. Resultados PIB departamental 2022 preliminar (Base 2015). Bogotá, D.C., 2022.

Díaz, Juan Felipe. "La propuesta de ciudadanía democrática en Hannah Arendt: Política y Sociedad". Revista Científica Complutense 5 (2013): 937-958.

Dthebault. "Biblioteca España, Medellin." October, 2013. https://beautifullibraries.wordpress.com/2013/10/10/biblioteca-espana-medellin/

Eagleton, Terry. La estética como ideología. Madrid: Editorial Trotta, 2006.

Fajardo, Sergio. "Discurso de Sergio Fajardo en la inauguración del Parque Biblioteca España." YouTube, March 13, 2007 de marzo. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SGwJxM26BV0&t=1s.

Fernández Osorio, Andrés Eduardo, and Yerlin Ximena Lizarazo-Ospina. "Crimen organizado y derechos humanos en Colombia: enfoques en el marco de la implementación del Acuerdo de Paz Con Las Farc-Ep." Novum Jus 16 (2): 215-250, 2022.

Filipe, Carolina, and Bernardo Ramírez. "Discursos, política y poder: el espacio público en cuestión." Territorios 35 (2016): 37-57.

Giraldo-Ramírez, Jorge, and Andrés Preciado-Restrepo. "Medellín, from Theater of War to Security Laboratory." Stability: International Journal of Security & Development 4 (2015): 1-14.

Glover, Jonathan. Humanidad e inhumanidad. Una historia moral del siglo XX. Madrid: Cátedra, 2001.

Gobbi, Juan. Flickr, 31 October, 2013. https://www.flickr.com/photos/morrissey/10965261034

Gómez, Sandra. Archdaily, 19 February, https://www.archdaily.co/co/02-6075/biblioteca-parque-espana-giancarlo-mazzanti

Holmes, Jennifer S., y Sheila Amin Gutiérrez de Piñeres. "Medellin's Biblioteca España: Progress in unlikely places." Stability: International Journal of Security & Development 2 (2014): 1-13.

Kant, Immanuel. Observaciones sobre el sentimiento de lo bello y lo sublime. Buenos Aires: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2004.

Mazzanti, Giancarlo. "La identidad latinoamericana no se da a través del lenguaje arquitectónico." ArchDaily, April 2015. https://www.archdaily.co/co/765822/entrevista-giancarlo-mazzanti

Medellín cómo Vamos. Informe de calidad de vida de Medellín. Medellín, 2019.

Medellín. Medellín cómo Vamos, 12 June, 2021. https://www.medellincomovamos.org/medellin

Montoya Restrepo, Natalia. "Urbanismo social en Medellín: una aproximación a partir de la utilización estratégica de los derechos." Revista Estudios Políticos 45 (2014), 205-222.

Narciso, Carlos Alberto, y Raúl Velasquez Buitrago. "Discursos, política y poder: el espacio público en cuestión." Territorios 35 (2016), 37-57.

Perafán del Campo, Eduardo Andrés, Sebastián Polo Alvis y Jessica Lizeth Caro Pulido. "Mirror box: ¿una reivindicación estética sobre el capital erótico de la mujer?". Revista Latinoamericana de Sociología Jurídica 1, no. 1 (2020): 183-206.

Perafán del Campo, Eduardo Andrés. "Estética, Ideología y Espacio Público." Utopía y Praxis Latinoamericana 25 (2020): 65-83.

Perafán del Campo, Eduardo Andrés. "La Desigualdad como Experiencia Estética: una corta reflexión para la sociología jurídica y política." Novum Jus 13, no. (1) (2019): 7-10.

Plata, Óscar P. "Externalidades ambientales ocasionadas por la urbanización en la ciudad de Medellín." Procesos urbanos 3 (2016): 38-54.

Rancière, Jacques. El desacuerdo: política y filosofía. Buenos Aires: Ediciones Nueva Visión, 1996.

Rancière, Jacques. El malestar en la estética. Buenos Aires: Capital Intelectual, 2011.

Scheck, David O. "Lo sublime y la reunificación del sujeto a partir del sentimiento: La estética más allá de las restricciones de lo bello." Signos Filosóficos 15 (2013): 103-135.

Scruton, Roger. La estética de la arquitectura. Madrid: Alianza Editorial, 1985.

Señal Colombia. "Maravillas de Colombia: Biblioteca España, Medellín." YouTube, 4 August 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pft1So0oVls.

Silva García, Germán, Fabiana Irala and Bernardo Pérez Salazar. "Das distorções da criminologia do Norte global a uma nova cosmovisão na criminologia do Sul". Dilemas 15, núm. 1 (2022): 179-199.

González Monguí, Pablo Elías, Germán Silva García, Angélica Vizcaíno Solano. "Estigmatización y criminalidad contra defensores de derechos humanos y líderes sociales en Colombia", Revista Científica Generaljosé María Córdova 20, núm. 37 (2022): 143-161.

Silva García, Germán. "La construcción social de la realidad. Las ficciones del discurso sobre la impunidad y sus funciones sociales", Via Inveniendi et Iudicandi 17, núm. 1 (2022): 105-123.

Silva García, Germán. "¿El Derecho Es Puro Cuento? Análisis crítico De La sociología jurídica Integral." Novum Jus 16, no. 2 (2022): 49-75.

Silva García, Germán y Johana Barreto Montoya. "Avatares de la criminalidad de cuellos blanco transnacional." Revista Científica General José María Córdova 20, núm. 39 (2022): 609-629.

Silva García, Germán y Vannia Ávila Cano. "Control penal y género ¡Baracunátana! Una elegía al poder sobre la rebeldía", Revista Criminalidad 64, núm. 2 (2022): 23-34.

Toro, Juan Ignacio, Carlos Vásquez Higuita, Mario Sánchez Vásquez, Esteban Mesa Toro, and Elkin Vargas González. "Santo Domingo Savio: un territorio reterritorializado." Territorios 22 (2010): 73-88.

Wacquant, Loïc. 1993. "Urban outcasts: stigma and division in the black American ghetto and French urban periphery." International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 15 (3): 366-383.

Weber, Max. Economía y sociedad: esbozo de sociología comprensiva. México: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1964/1922.

Home